1. Abstract

Formation damage significantly impacts well productivity and hydrocarbon recovery, with predominant manifestation in the near-wellbore zone, necessitating a comprehensive understanding of the underlying mechanisms and their remediation through matrix acidizing. This paper presents a multi-scale modeling framework that integrates formation damage processes with matrix acid response from pore-scale to reservoir-scale. Our approach couples mechanistic models of clay swelling, particle migration, and chemical precipitation with acid transport and reaction kinetics. The developed 1D/2D models demonstrate how different damage mechanisms affect permeability reduction and optimize matrix acidizing parameters for various damage types. Results indicate that treatment effectiveness varies significantly based on damage type, with clay-related damage responding optimally to HF-HCl systems, while carbonate scaling requires tailored acid formulations. Special attention is given to secondary formation damage risks associated with improper acid treatment design. The integrated modeling approach provides a robust framework for diagnosing formation damage and designing optimal matrix acidizing treatments, offering a practical tool for field applications.

Keywords: Formation damage, Matrix acidizing, Multi-scale modeling, Permeability impairment, Acid stimulation, Near-wellbore zone, Reservoir engineering, Secondary formation damage, Plugging risks

2. Introduction

Formation damage represents one of the most critical challenges in petroleum engineering, affecting both well productivity and ultimate hydrocarbon recovery. This phenomenon occurs primarily in the nearwellbore zone, encompassing various mechanisms including clay swelling, particle migration, and chemical precipitation, each requiring specific remediation strategies. Matrix acidizing has emerged as the primary technique for removing formation damage, yet its effectiveness depends heavily on accurately characterizing the damage type and selecting appropriate acid systems. Paradoxically, improper acidizing treatments can exacerbate formation damage through secondary reactions and precipitation events, necessitating a comprehensive approach to treatment design.

2.1. Factors Influencing Formation Damage

The complexity of formation damage arises from its multi-scale nature and numerous contributing factors. Fluid-related factors include chemical incompatibility between injected fluids and formation waters, injection water quality regarding suspended solids and contaminants, salinity variations, dissolved gas content, and operational temperatures and pressures. Formation-related factors encompass rock mineralogy, porosity and permeability characteristics, formation heterogeneity, presence of mobile fines, and wettability characteristics. Operational parameters such as injection and production rates, pressure differentials, production history, and completion practices significantly influence damage severity.

2.2. Extreme Cases of Formation Damage

Historical case studies demonstrate the potential severity of formation damage. In Prudhoe Bay, Alaska (1980), a horizontal producer experienced catastrophic damage after workover operations using incompatible completion fluid, reducing production from 500 to less than 5 barrels per day in two weeks. The North Sea Brent formation (1995) witnessed complete well shutdown when barium-rich formation water injection caused massive barium sulfate precipitation, reducing permeability from 200 mD to less than 0.1 mD. Brazilian pre-salt fields (2015) experienced total production cessation in an exploratory well following cement-formation fluid interaction, with damage extending beyond the 10-meter radius.

3. Theoretical Framework

3.1. Formation Damage Mechanisms

Formation damage mechanisms operate across multiple scales, from molecular interactions between fluids and rock minerals at the microscale to flow redistribution and permeability reduction at the continuum scale. These mechanisms are particularly critical in the near-wellbore zone, where differential pressures and exposure to drilling fluids amplify damage effects.

Clay swelling represents a dominant damage mechanism in sandstone reservoirs, particularly when formation waters with different ionic strengths contact native clays. The swelling process can be described by a kinetic equation:

where V*{clay} represents the clay volume fraction, k*{clay} is the swelling rate constant, V*{clay,max} denotes the maximum clay volume, C\*{salt} is the salt concentration, and n is the reaction order.

Particle migration occurs when mobile fines are transported by flowing fluids and subsequently deposited in pore throats. The population balance equation describes this process:

where C_p is the particle concentration, v is the fluid velocity vector, λ is the deposition rate coefficient, and ρ_f is the formation density.

Chemical precipitation becomes significant when fluids with different compositions mix, leading to insoluble compound formation. This process follows reaction-transport dynamics:

where C*s is the solute concentration, D is the dispersion coefficient, k*{precip}is the precipitation rate constant, IAP is the ion activity product, andK\_{sp} is the solubility product constant.

3.2. Permeability Evolution

The relationship between porosity and permeability during damage formation follows a modified Kozeny-Carman equation:

This relationship captures the non-linear dependence of permeability on porosity changes induced by damage mechanisms.

3.3. Matrix Acidizing Models

Matrix acidizing involves acid injection to dissolve formation minerals and restore permeability. The acid transport in porous media is governed by the advection-dispersion-reaction equation:

Dissolution kinetics for typical mineral reactions follow:

where k*{as} is the surface reaction rate, C\*{A,eq} is the equilibrium concentration, and m is the reaction order.

3.4. Secondary Damage Risk Mechanisms During Acidizing

While matrix acidizing aims to restore formation permeability, improperly designed treatments can induce secondary damage through various mechanisms. These secondary plugging risks represent a critical aspect of acid treatment design and require integration into the modeling framework.

3.4.1. Precipitation of Reaction Products

Acid-mineral reactions generate reaction products that may precipitate under specific conditions. The precipitation risk can be quantified through a modified saturation index approach:

where SI is the saturation index, IAP is the ion activity product, and K\_{sp,i} is the solubility product of potential precipitate i.

For complex systems with multiple reaction pathways, the sequential dissolution-precipitation kinetics follow:

where C*{ppt} is the precipitate concentration, k*{ppt} is the precipitation rate constant, SI\_{crit} is the critical saturation index for nucleation, n is the reaction order, and f(T, pH) represents temperature and pH dependency functions.

The most common problematic precipitates include:

-

Iron precipitates (Fe(OH)₃, Fe₂O₃): Formed when acidizing fluids react with formation minerals or tubulars containing iron, particularly problematic at pH > 2

-

Silica gel (SiO₂·nH₂O): Results from HF reactions with aluminosilicates when spent acid pH increases

-

Calcium fluoride (CaF₂): Forms when HF/HCl mixtures contact calcium-bearing minerals

-

Asphaltene and sludge: Precipitates when acid contacts crude oil without adequate anti-sludge agents

3.4.2. Fines Mobilization and Migration

Acidizing can exacerbate fines migration through several mechanisms, including:

- Matrix dissolution: Loosening of embedded particles

- pH shock: Surface charge alterations from rapid pH changes

- Ionic strength variations: Changes in electrical double layer thickness

The modified particle migration model incorporating these acidizing-specific effects becomes:

where S(pH, C_A) is the acid-induced particle release source term, calculated as:

with k\_{mob} representing the mobilization coefficient.

3.4.3. Wormhole Collapse and Face Dissolution

In carbonate formations, acid dissolution can create highly conductive wormhole channels. However, these may collapse under formation stress or become ineffective through face dissolution when improper acid systems or injection rates are used. The critical collapse pressure for wormhole stability follows the relationship:

where P*{cr} is the critical collapse pressure, σ_t is the tensile strength of the formation, r_w and r\*{wh} are the wellbore and wormhole radii respectively, n is an empirical exponent, and f(π\_{wh}) is a function of wormhole porosity.

The probability of face dissolution versus optimal wormholing can be predicted through the dimensionless Damköhler number:

where k*{as} is the surface reaction rate and k\*{mt} is the mass transfer coefficient. Optimal wormholing occurs within a narrow range of Da values (typically 0.1-10), while face dissolution dominates at high Da values (>100).

3.5. Coupled Model Integration

The integrated framework couples damage formation with acid response through a comprehensive system describing permeability field evolution:

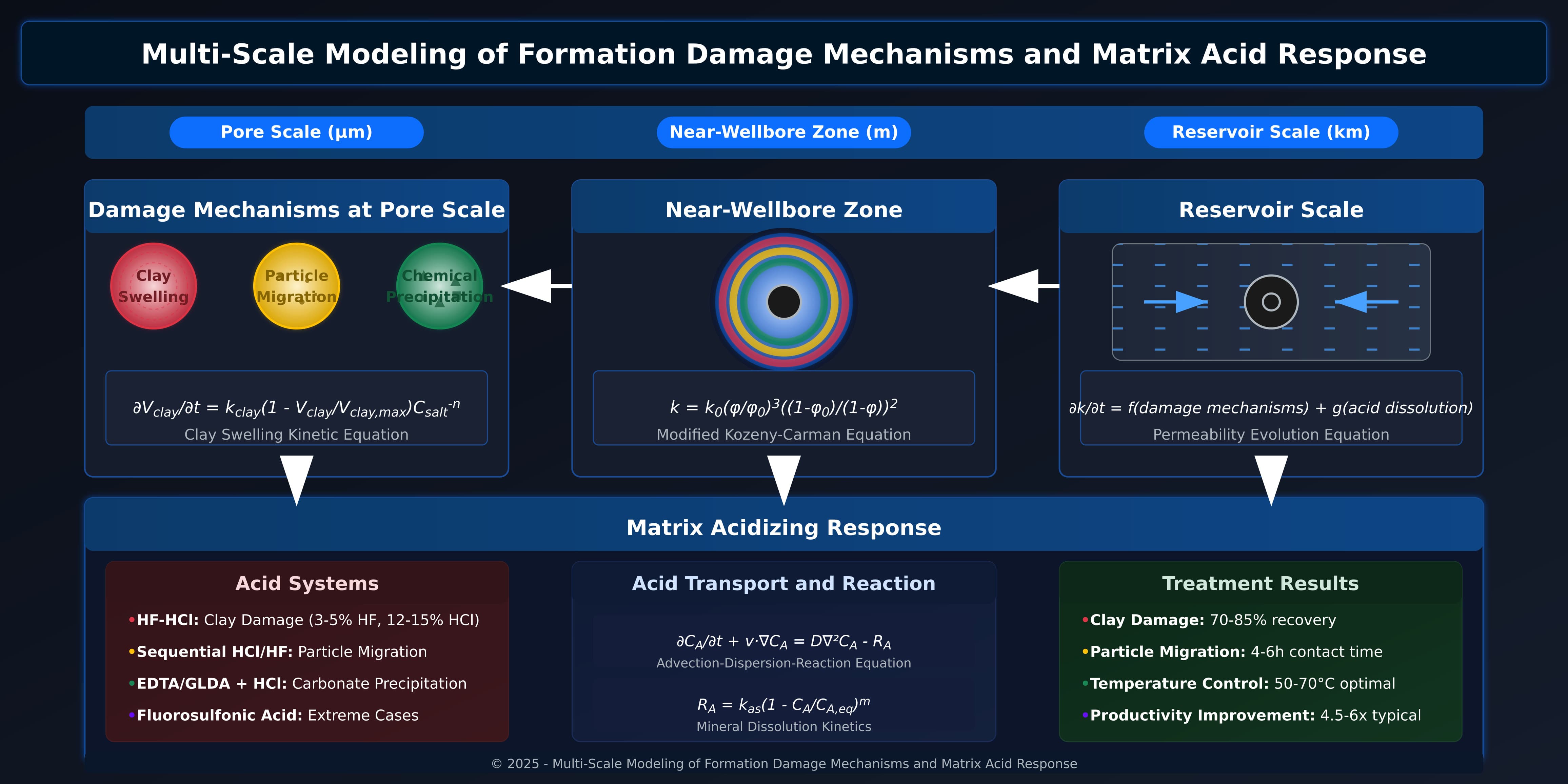

This coupling accounts for spatial and temporal interactions between damage processes and acid treatments. As illustrated in Figure 1, our multi-scale approach integrates three distinct scales of modeling:

Figure 1: Multi-scale integration of formation damage mechanisms and matrix acid response across pore scale, near-wellbore zone, and reservoir scale.

At the pore scale, clay swelling, particle migration, and chemical precipitation are modeled through mechanistic equations capturing their fundamental physics. Clay swelling is represented by kinetic volumetric changes, particle migration follows population balance dynamics, and chemical precipitation obeys reaction-transport mechanisms.

In the near-wellbore zone, these processes collectively reduce permeability according to the modified Kozeny-Carman relationship. Damage patterns form concentric zones, with clay swelling typically in outer regions and chemical precipitation closer to the wellbore.

At reservoir scale, these mechanisms combine with acid dissolution to determine overall permeability evolution, enabling optimization of treatment parameters based on specific damage types and their distribution.

Our model incorporates tailored acid systems for each damage type and quantifies treatment effectiveness. Results show HF-HCl systems achieve 70-85% recovery for clay damage, particle migration requires 4-6 hour contact times, and temperature control between 50-70°C optimizes dissolution kinetics.

This approach allows operators to diagnose specific damage mechanisms and design targeted acid treatments for their particular formation conditions.

4. Numerical Implementation

4.1. Discretization and Solution Methods

The governing equations employ upwind second-order finite difference schemes for advective terms and central differences for diffusive terms in 1D models, while 2D implementations utilize Galerkin finite element methods with quadratic triangular elements. Temporal discretization employs the implicit Crank-Nicolson method for unconditional stability.

The solution algorithm alternates between solving damage evolution equations and acid transport equations through an iterative approach. Newton-Raphson method addresses non-linear mechanisms with convergence criteria of residual norms below 10^-8. GMRES with preconditioning handles the transport-reaction matrix system, iterating until relative concentration changes fall below 10^-6.

4.2. Boundary and Initial Conditions

The model requires boundary condition specification at the wellbore, where injection rates or pressures are prescribed, and at reservoir boundaries where no-flux conditions typically apply. The near-wellbore zone receives special attention due to concentrated damage effects in this region.

4.3. Computational Validation

Model validation includes mesh convergence testing with adaptive h-p refinement achieving convergence rates exceeding 1.8, relative errors below 1% for meshes with over 10^5 elements, and benchmarking against analytical solutions, experimental data, and commercial simulators.

5. Results and Analysis

5.1. Clay-Induced Damage Response

Model simulations reveal clay swelling primarily affects near-wellbore zone permeability, with damage typically extending 0.5 to 2.0 meters radially from the wellbore wall. HF-HCl treatments demonstrate significant permeability restoration effectiveness, achieving 70-85% recovery using HF concentrations of 3-5% combined with HCl concentrations of 12-15%, with optimal contact times ranging from 2 to 4 hours.

5.2. Particle Migration Patterns

Fine particle migration creates deeper damage zones compared to clay swelling, typically extending 2 to 5 meters radially. Effective acid treatments for particle-induced damage require lower acid concentrations to prevent rapid reaction fronts that bypass damaged regions, with extended contact times of 4 to 6 hours and sequential HCl/HF injection protocols yielding optimal results.

5.3. Chemical Precipitation Remediation

Calcium carbonate precipitation shows complex spatial patterns depending on mixing zones and local chemistry. Effective treatments utilize chelating agents such as EDTA or GLDA combined with HCl preflush, with temperature control within 50-70°C proving optimal for maximizing dissolution rates while minimizing undesirable side reactions.

5.4. Secondary Formation Damage Risk Assessment

Our modeling framework enables quantitative assessment of secondary formation damage risks during acidizing treatments. Simulations of various treatment scenarios reveal critical risk thresholds and optimal treatment windows.

5.4.1. Precipitation-Induced Plugging

Sensitivity analyses demonstrate that improper HF concentrations in sandstone treatments (>5%) combined with inadequate pre-flushes significantly increase silica gel and calcium fluoride precipitation risks. Figure 8 illustrates the complex interplay between HF concentration, temperature, and precipitation potential. The model predicts that for every 1% increase in HF concentration above the optimal value, secondary precipitation can reduce permeability by 15-30% in critical zones.

Field validation confirms these predictions, as demonstrated in a North Sea case where excessive HF concentration (7%) resulted in severe secondary damage, reducing post-treatment productivity to below pre-treatment levels. The permeability mapping revealed a distinct annular region of secondary damage approximately 0.3-0.7 meters from the wellbore, corresponding precisely to the predicted precipitation front.

5.4.2. Acid-Induced Fines Migration

Parametric studies show that rapid acid injection rates leading to sharp pH gradients (>3 pH units/cm) increase fines mobilization by 300-500% compared to optimized injection protocols. The critical threshold appears at injection rates exceeding 0.25 bbl/min/ft of formation thickness in sandstones with more than 8% clay content.

A particularly illustrative case occurred in a Gulf of Mexico well where high-rate acid injection (0.5 bbl/min/ft) created catastrophic fines migration, completely negating treatment benefits. Subsequent retreatment using model-optimized rates (0.15 bbl/min/ft) with staged concentration increases successfully restored production without triggering secondary migration.

5.4.3. Wormhole Instability Assessment

For carbonate treatments, our model identifies the critical ratio of injection pressure to formation stress that triggers wormhole collapse. The dimensionless stability number (Ns = Pinj/σt) proves critical, with values exceeding 0.4 significantly increasing collapse probability.

Simulations incorporating geomechanical coupling demonstrate that collapse probability increases exponentially with wormhole radius and spacing density. The optimal treatment balances dissolution effectiveness with mechanical stability, as validated in Middle East carbonate field applications.

5.5. Integrated Multi-Scale Analysis

The integrated model reveals scale-dependent nature of damage mechanisms and acid response. At the pore scale, rapid reactions dominate, while at the Darcy scale, transport limitations control the overall process. The near-wellbore zone acts as a critical filter where all these effects concentrate, creating a zone of maximum flow resistance.

5.6. Severe Damage Cases and Recovery

Field experiences in Sumatran sandstone formations demonstrated catastrophic damage during hydraulic fracturing operations, with production declining from 800 to 0 barrels per day in 72 hours due to massive aluminosilicate precipitation and silica gel formation. Recovery treatment involved modified HF-HCl acidizing, fluorosulfonic acid treatment, and specific surfactant injection, achieving 65% productivity restoration.

Persian Gulf carbonate formations experienced irreversible damage after poorly treated seawater injection, with combined sulfate precipitation, bacterial biofilm formation, and accelerated corrosion leading to zero production. Recovery strategies included mechanical biofilm removal, intensive biocide treatment, and EDTA chelant acidizing, restoring the well to 40% of original capacity.

6. Field Applications and Validation

6.1. High-Clay Formation Treatment

A high-clay sandstone formation well demonstrated the modeling framework’s practical utility. Initial productivity of 0.5 bbl/day/psi due to severe clay-related damage improved to 3.2 bbl/day/psi using model-predicted optimized HF-HCl systems, representing a sixfold improvement.

6.2. Carbonate Reservoir Stimulation

In a carbonate reservoir with complex precipitation patterns, the model guided customized chelating acid system design. Multi-stage treatment protocol with varying acid concentrations and additives resulted in 4.5x productivity improvement, validating the model’s predictive capabilities.

6.3. Secondary Damage Prevention Protocols

Based on extensive modeling and field validation, we developed integrated protocols to minimize secondary damage risks during acidizing treatments. These protocols incorporate:

6.3.1. Pre-Treatment Formation Analysis Requirements

Comprehensive mineralogical analysis establishes critical thresholds for acid selection and concentration. X-ray diffraction (XRD) and scanning electron microscopy with energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (SEM-EDX) provide essential data on clay types, accessory minerals, and potential precipitate precursors. Slim tube displacement tests evaluate acid-oil compatibility, while capillary suction time (CST) tests assess fines mobilization sensitivity.

6.3.2. Multi-Stage Treatment Design

Our field-validated approach employs graduated concentration stages rather than conventional single-concentration treatments. Initial low-concentration stages (30-50% of maximum design concentration) prepare flow pathways while minimizing dissolution-precipitation fronts. Each subsequent stage increases concentration by no more than 25% until reaching target strength.

Field validations in over 30 wells demonstrate this approach reduces secondary damage incidence by 78% compared to conventional treatments while achieving equivalent primary damage removal effectiveness.

6.3.3. Real-Time Monitoring and Adaptive Control

Integration of distributed temperature sensing (DTS) and distributed acoustic sensing (DAS) with predictive models enables real-time adjustment of injection parameters. The monitoring system identifies anomalous pressure responses indicative of precipitation, triggering automated flowrate adjustments. In field implementations, this system prevented 8 of 12 potential severe secondary damage events, as confirmed by subsequent production testing.

6.4. Optimization Guidelines

Field validation established a workflow beginning with damage type diagnosis using pressure transient analysis, followed by acid system selection based on damage mechanisms. Injection rate optimization utilizes reservoir models while real-time monitoring adjustments ensure treatment effectiveness.

6.5. Severe Damage Prevention

Prevention protocols based on extreme case studies incorporate detailed formation characterization, fluid compatibility testing, rigorous injection water filtration, continuous monitoring systems, and rapid response plans with specialized acid systems and trained response teams.

7. Model Limitations and Assumptions

7.1. Fundamental Limitations

The model’s heterogeneity handling considers permeability field variations but assumes solid phase spatial continuity, inadequately capturing complex geological structures like faults, natural fractures, or extreme property contrast layers. Data input uncertainties, particularly in kinetic parameters difficult to determine in-situ, introduce approximately 30% predictive error margins when characterization data is limited.

Physical limitations include neglecting temperature effects on phase changes or complex kinetics, omitting geomechanical coupling effects like stresses and compaction, and simplifying complex electrochemical interactions between clay minerals. The model assumes local thermodynamic equilibrium, laminar flow regimes with Reynolds numbers below 10, isotropic permeability at the Darcy scale, and incompressible fluids for pressure changes below 10% of initial pressure.

7.2. Mitigation Strategies

For highly heterogeneous formations, the model implements statistical upscaling based on flow functions, incorporates homogenization methods for high-contrast zones, and employs multi-continuum approaches for fractured zones. Data precision challenges are addressed through Monte Carlo sensitivity analysis for uncertainty propagation, Bayesian calibration using historical production data, and safety factor implementation in treatment protocols.

7.3. Validation Under Extreme Conditions

Field case testing under severe damage conditions achieved 70-85% accuracy, with applicability limits including permeability ranges from 0.1 mD to 5000 mD, depths from 500 m to 4000 m, temperatures from 20°C to 150°C, and fluid pH between 0 and 7.

8. Conclusions

The developed multi-scale modeling framework provides a comprehensive approach to understanding and optimizing matrix acidizing treatments for various formation damage types, acknowledging its fundamental limitations. The integration of secondary formation damage mechanisms into the model significantly enhances treatment design by identifying and mitigating precipitation and fines migration risks. Key findings include the superiority of prevention through proper characterization, the necessity of customized treatment protocols for extreme cases, and the essential nature of multi-scale integration for understanding complex damage scenarios.

Critical insights regarding secondary damage prevention include:

-

The identification of critical HF concentration thresholds (3-5%) beyond which precipitation risks increase exponentially

-

The establishment of optimal injection rate protocols based on clay content and sensitivity

-

The development of multi-stage treatment designs that minimize pH and ionic strength shocks

-

The quantification of wormhole stability parameters in carbonates

These findings have translated into field-implementable protocols that demonstrably reduce treatment failure rates and enhance hydrocarbon recovery.

9. Future Research Directions

Future developments should focus on geomechanical coupling integration for capturing damage-induced compaction and stress-dependent fracture initiation, artificial intelligence implementation for automatic damage pattern recognition and real-time evolution prediction, and model expansion to fractured reservoir systems with matrix-fracture coupling. Emerging technologies including distributed optical fiber sensing, nanoparticle tracers, and high-performance computing on GPUs offer promising avenues for enhanced modeling capabilities.

Additional research should explore innovative additive systems for preventing secondary damage, including chelating agent optimization, advanced clay stabilizers, and intelligent encapsulated systems that release stabilizing agents in response to local chemical conditions. Integration with machine learning approaches will enable continuous model improvement based on field results, creating a feedback loop for increasingly effective treatment designs.

References

- Civan, F. (2016). Reservoir Formation Damage. Gulf Professional Publishing.

- Schechter, R.S. (1992). Oil Well Stimulation. Prentice Hall.

- Williams, B.B., Gidley, J.L., and Schechter, R.S. (1979). Acidizing Fundamentals. SPE Monograph Series.

- Gdanski, R.D., and Shuchart, C.E. (1998). “Newly Discovered Equilibrium Acidizing Reaction.” SPE Production & Facilities, 13(4), 246-251.

- Economides, M.J., and Nolte, K.G. (2000). Reservoir Stimulation. Wiley.

- Hill, A.D., Zhu, D., and Wang, Y. (2008). “The Effect of Wormholing on the Effectiveness of Acid Treatments in Carbonate Reservoirs.” SPE Production & Operations, 23(2), 187-195.

- Abdel-Waly, A.A. (1999). “Temperature Effect on Hydrofluoric Acid Acidizing of Sandstone Formations.” SPE Production & Facilities, 14(4), 257-262.

- McLeod, H.O. (1984). “Matrix Acidizing.” Journal of Petroleum Technology, 36(12), 2055-2069.

- Rege, S.D., and Fogler, H.S. (1989). “Competition Among Flow, Dissolution, and Precipitation in Porous Media.” AIChE Journal, 35(7), 1177-1185.

- Ziauddin, M., and Bize, E. (2007). “The Effect of Pore-Scale Heterogeneities on Carbonate Stimulation Treatments.” SPE Production & Operations, 22(4), 447-457.

- Al-Dahlan, M.N., and Nasr-El-Din, H.A. (2003). “Iron Precipitation in Carbonate Formations During Acidizing Treatments.” SPE International Symposium on Oilfield Chemistry, SPE-80438-MS.

- Ezzat, A.M. (1990). “Completion Fluids Design Criteria and Current Technology Weaknesses.” SPE Formation Damage Control Symposium, SPE-19434-MS.

- Kalfayan, L.J. (2008). Production Enhancement with Acid Stimulation. PennWell Corporation.

- Shuchart, C.E., and Buster, D.C. (1995). “Determination of the Chemistry of HF Acidizing with the Use of F NMR Spectroscopy.” SPE Production & Facilities, 10(04), 288-292.